As an ambassador for Samad’s House, Cheryl Jones recently organized tables outside Franciscan Peacemakers on Lisbon Avenue in the Walnut Hill neighborhood on Milwaukee’s Near West Side. Samad’s House is one of the Midwest’s leading residential facilities for women in recovery. That morning, like so many others, Jones was there to counsel residents on harm reduction—offering tools, resources, and services designed to prevent drug overdose deaths and keep users safe.

A woman wandered by, eyeing the table. “What’s in the bags?” she asked.

Jones had heard this question countless times before. Her usual response was straightforward: she’d explain the contents—naloxone, a life-saving medicine that reverses opioid overdoses; fentanyl test strips to detect the deadly synthetic compound in street drugs; and gun locks to prevent accidental shootings. But too often, the response was met with shame. “I don’t use drugs,” people would say, turning away. They wouldn’t take the bags, Jones explained, because they were too embarrassed to admit they might need them.

But at 63, Jones had learned to adapt. That day, she tried a new approach. “I know you don’t use drugs,” she said gently. “But everyone knows someone—a family member, a friend, a neighbor—who does. Naloxone and test strips can save lives. Take them. Let me teach you how to use them. You could save someone’s life.”

Within an hour, Jones distributed 30 harm-reduction bags.

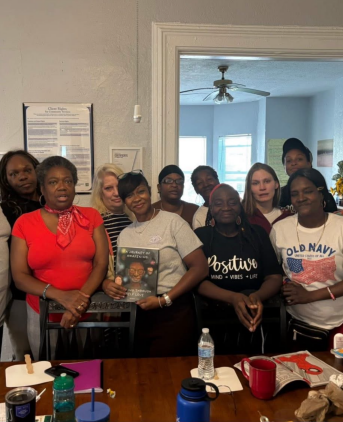

This is precisely what Samad’s House Founder and CEO, Tahira Malik, envisions for her ambassadors. Malik, a former drug user herself, has built an ambassador program that empowers women who’ve walked the path of addiction and recovery to become trusted messengers in their communities. “Our ambassadors use their street smarts and lived experiences to teach others about harm reduction,” Malik says. “They save lives. They address the overdose crisis that has devastated Black families and communities in Milwaukee.”

The ambassadorship program, launched five years ago, is a cornerstone at Samad’s House. The ambassadors—graduates of the recovery program—are trained to use naloxone, fentanyl test strips, and other harm reduction tools. They go into neighborhoods, meeting people where they are, offering not just resources but hope. “They’ve lived it,” Malik says. “They know what it’s like to be judged, stigmatized, and written off. That gives them a level of empathy and compassion that can’t be taught.”

Malik’s voice tightens as she reflects on the stakes. “Just because someone is still living in addiction doesn’t mean they have to die,” she says. “We’ve lost so many people because they didn’t know fentanyl was in their drug supply. One dose, and their life was snatched away.”

Moreover, Malik says the ambassadors are trusted, credible messengers in the community because they are former users, and the people relate to them. “Our ambassadors help people navigate what they are going through, maybe recovery, or maybe just into having and using harm reduction resources so they can live another day,” Malik adds.

While Samad’s House ambassadors and other harm reduction initiatives in Milwaukee have made significant strides, there is an urgent need for sustained funding for Samad’s House and other organizations. Federal budget cuts and restrictions on harm reduction programs have created concerns in Milwaukee and communities across the country. Harm reduction includes naloxone distribution, fentanyl test strips, and medication-assisted treatment. These compassionate, evidence-based approaches meet individuals where they are, prioritizing dignity and practical support.

But the Federal Government has returned to opposing many harm reduction strategies, often favoring a punitive, abstinence-focused “War on Drugs” approach. Proposed and enacted federal budget cuts have hampered harm reduction efforts by reducing funding for agencies such as the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The government has also stiffened restrictions on how funds can be used.

Between 2000 and 2023, at least 14,747 Wisconsin residents died from overdoses. Milwaukee County experienced a 30% drop in overdose deaths in 2024, thanks to innovative community efforts and local investments, including $34 million from opioid settlement funds. But the racial disparity in overdose deaths persists. In 2024, Black residents in Milwaukee County experienced a fatal overdose rate of 76 per 100,000 people—nearly double the rate for White residents, even though drug usage in Black and White communities is similar. Black residents accounted for 42% of overdose deaths, despite making up only 27% of the population.

Noting the decline in overdose deaths in 2024, Malik maintained that fatalities will rise again if “funding is lost or reallocated.” Malik adds, “We will go back to the crisis where we had so many drug fatalities. We were having more drug deaths than homicides and accident victims. Is that what we want as a society? Do we want agencies and organizations to be unable to raise awareness and provide education because funding is no longer available? Do we want programs like the Samad House ambassadors to go away?”

For Jones, harm reduction work is deeply personal. Her husband passed away in October 2023 from liver cancer, a loss that sent her spiraling into drug use. “I just got really crazy,” she says. “I was in a hospital for seven days. They were going to release me, but I told them no, I was on drugs and needed help. I went into rehab and learned about harm reduction. I was broken, I was lost, I was confused. I was violent. I was there for nine months, and they put me back together.”

Eventually, with the help of harm-reduction resources, Jones went to Samad’s House, completed their program, and was hired as an ambassador to support others. Now, she’s on the front lines, helping others find the hope and resources that saved her.

“I love my job that I do now because I love people,” Jones says. “I love people a lot. I love working on harm reduction and helping save lives.”